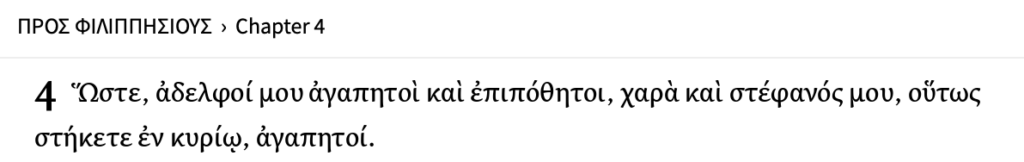

Greek (NA/UBS tradition):

Ὥστε, ἀδελφοί μου ἀγαπητοὶ καὶ ἐπιπόθητοι, χαρὰ καὶ στέφανός μου, οὕτως στήκετε ἐν κυρίῳ, ἀγαπητοί.

Where does Philippians 4:1 sits in the rest of the book?

Philippians 4:1 is not a random inspirational line. It is a hinge verse, a conclusion to the argument in 3:17–21 and a bridge into the concrete pastoral instructions that follow (especially 4:2–3, the conflict between Euodia and Syntyche).

In Philippians 3, Paul has been building two large contrasts:

(1) imitation vs. destructive models, and

(2) earthbound identity vs. heavenly citizenship.

He climaxes with a strong identity statement: the church’s πολίτευμα (commonwealth/citizenship) is in heaven and they await the Savior who will transform them.

This matters because “stand firm” here is not generic grit or a personality-driven resilience. It is eschatologically anchored, or end-times focused, perseverance: hold steady because your identity, future, and allegiance are already located “in the Lord.”

Philippians 4:1: Historical context

Philippi: a Roman-flavored city shaping a Christian community

Philippi was a significant Roman colony in Macedonia. Colonies tended to reproduce Roman civic culture: status, honor, loyalty, public virtue, patronage networks, and strong group identity. That background helps you feel the force of Paul’s “citizenship” language in 3:20 and his repeated emphasis on unity and “one-mindedness” across the letter.

Paul’s situation in Philippians: pastoral authority under pressure

Paul writes Philippians while imprisoned (the letter repeatedly references his chains and the progress of the gospel despite confinement).

That setting creates a paradox: Paul is physically restrained, yet he calls the church to stability and courage.

His exhortation to “stand firm” is not armchair advice, it comes from someone practicing endurance under real constraint.

Philippians 4:1 Church dynamics: affection, conflict, and public witness

Philippians reads like a warm letter to a beloved church with real stresses: social pressure, internal friction, and the ever-present lure of status-based comparison.

Philippians 4:1 functions as a pastoral compression point:

intense affection (“beloved,” “longed-for,” “my joy and crown”) combined with a clear imperative (“stand firm”).

Philippians 4:1: Literary context and rhetorical strategy

Paul stacks vocatives and affectionate labels before he issues the imperative. That sequence is not decorative; it’s persuasive strategy.

He is doing at least four things at once:

First, he reasserts relational bonds. The church is not a project; it’s family (“brothers and sisters”), desired (“longed-for”), and valued.

Second, he frames obedience as identity-consistent. The imperative is not “be better,” but “live like who you are.”

Third, he uses honor imagery to stabilize behavior. Calling them his “joy and crown” publicly locates their faithfulness as his “boast” or “victory wreath.” In Greco-Roman moral persuasion, that kind of honor language can strengthen group cohesion.

Fourth, he narrows the mode of steadfastness: “in the Lord.” This is not Stoic self-mastery; it’s covenantal loyalty and union-based perseverance.

Philippians 4:1: Clause-by-clause Greek parsing and syntax

ὥστε — “therefore / so then”

ὥστε is an inferential connector. In many contexts it can introduce result (“so that”), but here it functions naturally as a logical conclusion: given what I just said, here’s what follows. The argument immediately preceding (3:17–21) strongly supports the inferential “therefore.”

ἀδελφοί μου — “my brothers (and sisters)”

ἀδελφοί is vocative plural, commonly used inclusively for the community. μου (“my”) intensifies belonging, Paul is not distancing; he’s claiming relationship.

ἀγαπητοὶ καὶ ἐπιπόθητοι — “beloved and longed-for”

Both are adjectives used vocatively (addressing the church directly).

- ἀγαπητοί: “beloved,” carrying covenantal warmth. Paul uses it to signal secure relational standing, not conditional approval.

- ἐπιπόθητοι: “longed-for,” a strong emotional term. It communicates absence + affection + desire for reunion. This word choice matters because it makes the imperative land inside tenderness, not threat.

χαρά καὶ στέφανός μου — “my joy and my crown”

Again, nominal phrases functioning vocatively, Paul is effectively saying, “You are my joy; you are my crown.”

- χαρά: joy not merely as emotion but as relational delight and gospel-fruit.

- στέφανος: the victor’s wreath/crown (not typically the royal diadem). The imagery evokes public honor attached to victory, perseverance, and worthy performance. Paul is treating their perseverance as the “evidence” of his labor’s success.

οὕτως στήκετε — “stand firm in this way”

This is the command core.

- στήκετε: present active imperative, 2nd person plural of στήκω. Present imperative typically carries an ongoing sense: keep standing firm / continue to stand firm, not a one-time heroic burst.

- οὕτως (“thus / in this way”) is crucial. It can point backward (“in this way” meaning: by following the model and citizenship ethic of 3:17–21) and forward (“in this way” meaning: as I’m about to lay out for you in 4:2–9). The best reading is often both: it gathers the whole pattern-identity in Christ, imitation of faithful models, and the practical unity/peace disciplines that follow.

ἐν κυρίῳ — “in the Lord”

This prepositional phrase is the theological anchor. “In the Lord” in Paul typically signals union/participation and sphere of life: steadfastness happens within the relationship, power, and allegiance of the risen Jesus, not merely “for” the Lord but “in” him.

ἀγαπητοί (used again) — “beloved”

The repetition frames the imperative with affection. It’s like Paul bookends the command with love so the community hears exhortation as care, not domination.

Philippians 4:1: Lexical analysis

στήκετε (στήκω) — “stand firm / hold your ground”

This verb carries the picture of someone not yielding position under pressure. It’s stability under external force and internal drift. In Pauline usage, “standing” is often paired with perseverance, unity, and resistance to distortions.

Practical nuance: Paul’s “stand firm” is not “be stubborn.” It’s “don’t be moved off the gospel center.” A church can be “unyielding” about preferences and still be unstable in the Lord. Paul targets gospel-ground, not ego-ground.

ἐν κυρίῳ — “in the Lord”

This phrase prevents two common errors: moralism (“stand firm by trying harder”) and tribalism (“stand firm by circling wagons”). “In the Lord” means the source, sphere, and standard of firmness is Christ.

στέφανος — “crown (victor’s wreath)”

This is achievement/honor imagery, but not self-congratulation. Paul uses the church’s perseverance as his “crown” because it represents gospel fruit. It also subtly calls the church upward: “You are my crown, live like it.” That is not manipulation; it’s relational honor as moral formation.

ἐπιπόθητος — “longed-for”

This is emotionally expensive vocabulary. It signals that Paul’s leadership is not transactional. That matters for application: the tone of exhortation should match the text—warm, relational, identity-based.

Philippians 4:1 Commentary

What Paul is doing

He is consolidating identity, affection, and eschatological hope into a single pastoral directive: stability in Christ.

He is also preparing the ground for addressing conflict (4:2–3). Steadfastness will include repairing relationships, not just resisting persecution. “Stand firm” is as much about internal coherence as external pressure.

He is shaping community ethos. The church in a Roman colony would feel pressure to adopt the surrounding status games. Paul’s “joy and crown” language relocates honor: not in Roman rank, but in gospel-shaped faithfulness.

What Paul is not doing

He is not telling them to “stand firm” by winning culture wars, dominating opponents, or becoming harsh. The verse contains zero aggression vocabulary. The firmness is explicitly “in the Lord,” which in Philippians repeatedly looks like humility, unity, and Christlike self-giving (especially framed by Philippians 2).

He is not teaching a “power-through” spirituality where feelings don’t matter. Ironically, he names feelings constantly, joy, longing, affection, while calling for stability.

Philippians 4:1 Interpretive options with pros and cons: A critical approach

Option A: “οὕτως” points mainly backward (to 3:17–21)

Claim: “Stand firm like this: imitate faithful models, reject destructive patterns, remember your heavenly citizenship.”

Pros: Strong logical continuity; honors the “therefore” as a conjunction; makes 4:1 a clean conclusion to the citizenship paragraph.

Cons: Can underplay the fact that 4:2–9 gives very concrete “how-to” practices that look like the outworking of “stand firm.”

Option B: “οὕτως” points mainly forward (to 4:2–9)

Claim: “Stand firm like this: reconcile, practice prayer, pursue peace, think on what is excellent.”

Pros: Fits the immediate shift into interpersonal exhortation; highlights that steadfastness is practiced through unity and disciplined thought/prayer.

Cons: Risks weakening the strong inferential tie to 3:20–21 and the identity logic that fuels the command.

Best synthesis

Read “οὕτως” as a deliberate hinge that points both directions: the church stands firm by grounding identity in the Lord (3:17–21) and expressing that identity through embodied practices of unity, prayer, and holy attention (4:2–9). This reading is rhetorically elegant and pastorally realistic: worldview and practices belong together.

Theological themes packed into one verse

Philippians 4:1 compresses a theology of perseverance that is (1) christocentric, (2) communal, (3) eschatological, and (4) affection-driven.

Christocentric: steadfastness exists “in the Lord,” not in personality traits.

Communal: every address term is plural and familial. Perseverance is corporate.

Eschatological: it is rooted in the “therefore” of 3:20–21 (future transformation and allegiance to Christ).

Affection-driven: Paul motivates with love and honor, not threat.

Philippians 4:1 Application: how “stand firm in the Lord” becomes concrete

Personal discipleship (identity stability)

“Stand firm” begins as refusing identity drift. You can’t stand firm in the Lord while building your selfhood on performance, applause, outrage, or comfort. A practical diagnostic is: What destabilizes me fastest? That often reveals the real “lord” you’re standing in.

Emotional resilience (without pretending you’re fine)

Paul’s affection language makes room for longing and pain. Standing firm is not emotional numbness; it’s continued allegiance in the middle of real feeling. The mature move is to locate your emotional weather inside “in the Lord,” not outside it.

Church unity (steadfastness includes repair)

Because 4:1 leads directly into conflict repair (4:2–3), the most faithful “application” is often relational: pursue reconciliation, refuse factionalism, and treat unity as a gospel issue rather than a personality preference.

Leadership posture (how to exhort well)

Paul models exhortation that is warm, specific, and identity-based. If your leadership style cannot say “beloved” before “stand firm,” you’re not imitating this verse’s tone. The verse implicitly critiques harsh, control-oriented leadership masquerading as “conviction.”

Public witness (honor relocated)

In a status-shaped environment (ancient or modern), “crown” imagery relocates pride: the community’s faithfulness becomes the honor. In modern terms, the “win” is not optics; it’s perseverance in Christlike integrity.

Philippians 4:1 Conclusion

Philippians 4:1 is a powerful exhortation that combines theological hope with intense personal love. Paul calls the church to spiritual resilience, not through grit, but through their union with Christ and their identity as citizens of heaven. It reminds us that standing firm is a communal act, fueled by love and anchored in the hope of the gospel.

Community events site – News and updates are showcased well, making participation straightforward and engaging.